Should South Korea sustain its present levels of productivity, its potential economic growth rate—which signifies the fastest pace at which an economy can expand without causing inflation—could drop to zero by 2040 as predicted by the Korea Development Institute (KDI), with projections indicating it may turn negative later this decade. This somber prediction marks a substantial adjustment compared to estimates made three years prior when the institute anticipated that the growth rate would reach its lowest point only by 2050—a timeframe that has now advanced by ten years.

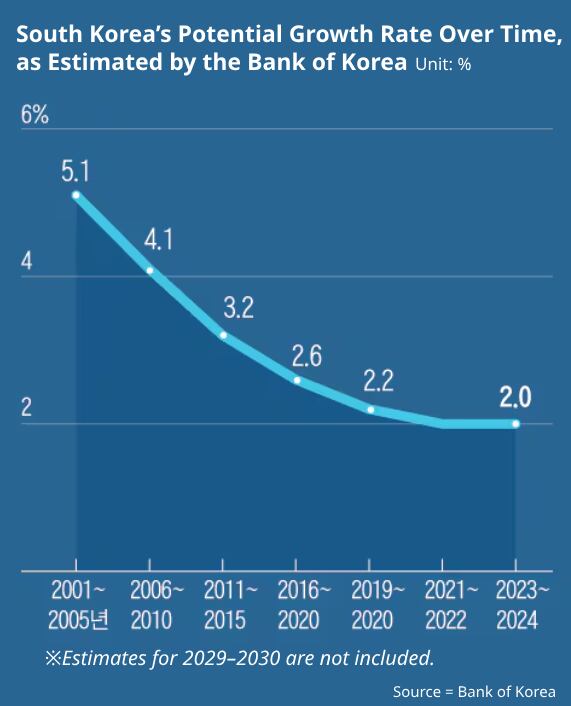

In the beginning of the millennium’s second decade, South Korea experienced a potential growth rate close to 5%; however, over time, this figure has diminished to about 2%. It is further estimated that this trend will persist, leading the growth rate to decrease until it reaches zero approximately fifteen years henceforth.

The ongoing downturn is broadly attributed to an economically inefficient and costly system, hindered by overly burdensome corporate regulations and escalating labor expenses that have diminished overall productivity. This situation is exacerbated by swift demographic changes like population aging and a falling birthrate, factors that typically lie outside the scope of effective policymaking. Despite this, experts suggest that South Korea might rejuvenate its economic prospects via deregulation, fostering new industry sectors, and implementing supportive measures for businesses. In comparison, the U.S., with an economy approximately fifteen times larger than South Korea’s, sustains a possible growth rate of 2.1%. The Korean Development Institute (KDI) attributes this favorable outlook partly to substantial investments in burgeoning fields including AI, big data, and blockchain technologies.

In order to avoid slipping into inertia, KDI advised the government to create an environment conducive for innovative companies to penetrate new markets, encourage competition by loosening regulatory restrictions, and enhance productivity via changes to the salary structure and working hours legislation.

These recommendations are not novel; they have existed for quite some time but consistently stall due to powerful vested interests and a political system that frequently values short-term wins over comprehensive changes. The Bank of Korea (BOK) has downgraded its economic growth projection for this year to 1.5%. In an acknowledgment, Governor Rhee Chang-yong stated, “This reflects the current state of our economy,” blaming the sluggishness on the nation’s reluctance to embrace reforms or foster innovative sectors, opting instead to stick with outdated industries.

South Korea can glimpse the potential outcomes of a stagnant economy by examining Japan’s “three lost decades.” In contrast to Japan, which underwent modernization almost a hundred years prior and has had access to substantial national reserves, South Korea does not have such an advantage. Should the nation experience an extended phase of slow economic growth, the repercussions might be considerably harsher. It is imperative that the era of populism comes to a close.

Leave a Reply